The Architect Lawyer: Who Will Control the Next Front Door?

The legal profession isn’t being disrupted. It’s being redesigned. The question is whether lawyers will be the architects—or the blueprints.

The Front Door Is Moving

For over a century, the front door to legal services was a conversation with a human attorney. A handshake. A retainer. A relationship.

That front door is now a prompt.

Google’s AI Overviews answer “Do I need a lawyer for a first DUI in Texas?” before the user ever sees a law firm’s website. ChatGPT drafts NDAs. Harvey redlines merger agreements. Ironclad measures success by contracts that close without legal review.

The invisible constraint people always forgot? Lawyers were never selling expertise. They were selling access. Access to knowledge locked behind bar exams, Latin phrases, and $1,500-per-hour gatekeeping.

AI didn’t kick down the front door. It built a new one.

And if you think this is hypothetical: that AI is hype, that it won’t affect your practice, that the legal profession is somehow immune, let me show you what happened to an industry that thought the same thing.

The Travel Industry Wrote Your Future: A Case Study

Jamin Ball is a cloud software analyst at Altimeter Capital. He doesn’t follow the legal industry. He follows what happens when software reshapes how customers access services. And he identified a pattern that should terrify every lawyer who thinks AI is “just hype.”

Ball distinguishes between two types of software in any industry:

System of Record (SoR): The database where truth is stored

Front Door: The interface where work is initiated

For decades, the travel industry’s System of Record was the Global Distribution System—the database connecting airlines, hotels, and rental cars. Companies like Sabre and Amadeus built this infrastructure.

But the front door? That was the travel agent.

Travel agents were the human interface. They knew how to navigate the GDS systems. They understood fare classes, routing rules, and booking codes that were impenetrable to ordinary consumers. They translated complexity into action. You told them where you wanted to go; they made it happen.

Sound familiar?

Then Expedia and Booking.com arrived.

These online travel agencies didn’t build better databases. They didn’t own hotels or fly planes. They did one thing: they replaced the human interface with a software interface. They became the place where customers started their journey—and they cut the travel agent out entirely.

The results?

Booking Holdings, New Front Door: Market Cap: $164 Billion

Sabre, System of Record: $477 Million

Read that again. The company that owns the interface is worth 344x more than the company that owns the system of record.

Sabre still processes reservations. Amadeus still runs the backend. But they’ve been reduced to utilities—commoditized pipes that the front door companies pay pennies to access.

The travel agents disappeared.

Remember travel agents? They were the human gatekeepers—the licensed professionals who knew the systems, understood the options, and guided you through complexity. For decades, you couldn’t book a flight or hotel without going through them.

Expedia didn’t just digitize what travel agents did. It replaced them entirely. The number of travel agents in the U.S. dropped from 124,000 in 2000 to around 60,000 today—and those who remain serve narrow niches that software can’t easily replicate.

Want a concrete example? In 1994, Carlson Wagonlit Travel became the largest travel agency in the world with approximately $9 billion in revenue. They were the Kirkland & Ellis of travel—the dominant player, the gold standard. In 2025, they were sold to Amex Travel for $570 million. That’s a 94% collapse in value over three decades.

The travel agents were the lawyers of the travel industry. They were the front door. And when software built a better door, even the biggest players got locked out.

This is what Ball calls “value inversion.” When software captures the interface, the interface captures the economics—and the human gatekeepers become optional.

Now Apply This to Law

The legal industry is a $1 trillion global market. In the U.S. alone, law firms generate over $350 billion annually.

For over a century, the “front door” to this market was a conversation with a licensed attorney. Lawyers were the interface. The System of Record—case law, statutes, regulations—sat behind them, accessible primarily through expensive databases like Westlaw and LexisNexis.

The structure looked like this:

Client → Lawyer (Front Door) → Legal Research (System of Record) → Legal Work Product

Lawyers controlled the interface. They decided what questions to research, what precedents mattered, what arguments to make. The System of Record was powerful, but it required a lawyer to access and interpret it.

AI inverts this structure.

Client → AI Interface (New Front Door) → Lawyer (Backend Resource) → Legal Work Product

When a client asks Harvey to “review this merger agreement and flag the five biggest risks,” Harvey doesn’t call a lawyer. It accesses the legal knowledge base, applies reasoning, and delivers output. A lawyer might review that output—but the lawyer is now downstream of the interface, not upstream.

This is the travel industry pattern repeating. Harvey et al becomes Booking.com. The law firms become Carlson Wagonlit. The lawyers become the niche travel agents.

The Numbers That Should Wake You Up

Kirkland & Ellis—the most profitable law firm on the planet—generated $8+ billion in revenue in 2024.

A legal AI startup with a fraction of Kirkland’s revenue commands a valuation equal to the firm’s entire annual output.

Investors aren’t stupid. They see the travel industry playbook. They’re betting these companies become the Booking.com of legal—capturing the interface, reducing law firms to backend fulfillment.

The math is brutal. Law firms scale like restaurants. Legal AI scales like Netflix.

The $1 Trillion Question

The global legal market is worth $1 trillion. But here’s the number hiding inside that figure:

85% of Americans with civil legal needs can’t afford a lawyer.

That’s not a gap in the market. That’s the majority of the market—structurally locked out by a business model that requires $300-$2000+/hour humans for every interaction.

The $1 trillion we measure today represents only the people and businesses who can pay current prices. The actual demand—the people who need wills, tenant disputes resolved, small business contracts reviewed, employment issues addressed—is multiples larger.

AI doesn’t just threaten the existing $1 trillion. It unlocks the market that was never accessible.

This is why LegalZoom has an Arizona ABS license and a partnership with Perplexity that moves the legal front door to the search bar. This is why Rocket Lawyer built “Rocket Copilot” with seamless human handoff. They’re not competing for the $1 trillion. They’re competing for the $3-4 trillion that could exist if the unit economics worked.

DoNotPay is the cautionary tale—the FTC forced a $193K settlement for unsubstantiated “Robot Lawyer” claims. Pure AI without human guardrails faces regulatory risk. But the winning model isn’t AI or lawyers. It’s AI with lawyers in a fundamentally different role.

Three Layers of Displacement

The front door isn’t moving in one direction. It’s fragmenting across three distinct layers—and each requires a different response.

Layer 1: BigLaw — The Associate Is Already Gone

At elite firms, Harvey et al are doing what first-year associates used to do: document review, initial research, redlining. Thomson Reuters’ “Deep Research” agent doesn’t just search—it plans research paths, executes them, and verifies its own citations.

The firms positioning this as “augmentation” are telling a half-truth. Yes, the associate still reviews the output. But the associate used to generate the output. That’s not augmentation. That’s substitution with a human checkpoint.

The honest question: How many associates does a team need when the AI handles 80% of the volume?

Layer 2: In-House — The General Counsel Faces a Two-Front War

Front one: Platforms like GC AI and Eudia promise that one general counsel can do the work of three. Eudia went further—they became a regulated law firm under Arizona’s ABS rules. They don’t sell hours. They sell outcomes. Their “Company Brain” captures institutional knowledge so it never walks out the door.

Front two: Business units are building their own doors. Ironclad’s “No-Touch Rate” celebrates contracts that close without legal involvement. LinkSquares lets sales managers type “Make this indemnification mutual” and the AI executes. Streamline AI triages 60-70% of intake requests before a human lawyer ever sees them.

The general counsel’s job used to be controlling legal risk. Increasingly, it’s controlling access to legal resources. And the business is building bypass routes.

Layer 3: Consumer — The Door Is Wide Open

Remember that 85% who can’t afford lawyers? They’re not waiting for the bar association to solve access to justice. They’re using ChatGPT. They’re using Google’s AI Overviews. They’re getting answers—imperfect answers, sometimes dangerous answers—because imperfect answers beat no answers.

The platforms that figure out how to serve this market with AI plus appropriate human oversight won’t just capture market share. They’ll create a market that never existed.

The Architect Lawyer Emerges

So what’s the role that survives—and thrives—when the front door moves?

It’s not the lawyer who knows the most case law. AI has that covered.

It’s not the lawyer who drafts the fastest. AI drafts faster.

It’s not even the lawyer with the best client relationships—because the client relationship is migrating to whoever owns the interface.

The role that survives is the Architect Lawyer.

The Architect Lawyer is software literate—and that literacy pays dividends in two phases.

Phase 1: Today — Buy and Use Technology More Effectively

Right now, software literacy means understanding how technology works well enough to:

Buy smarter: Evaluate which platforms actually deliver vs. which are vaporware. Know the right questions to ask vendors. Understand what’s technically possible vs. what’s marketing.

Use dynamically: Go beyond the default settings. Design prompts that get reliable outputs. Chain tools together for complex workflows. Customize platforms to your practice.

Guide strategy: Understand where technology is heading so you can position your firm, your team, or your career accordingly.

This is table stakes. The lawyers who can’t do this will overpay for tools they underuse, while competitors extract 10x the value from the same technology.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

Phase 2: Tomorrow — Design Solutions That AI Fabricates

Consider how the semiconductor industry works.

Nvidia doesn’t manufacture chips. They design them. So do huge teams at Apple with their M class chips, and thousands more in companies of all sizes. Where does the fabrication plant sit? Well the one that can do the most advanced work, TSMC, is just fine. The one’s that have become commodity driven, Intel et al, falling behind.

The designers capture a significant portion of the value chain.

AI models are becoming the “fabs” of the software world. Today, if you want a custom legal intake system, you hire developers, wait months, and pay six figures. Tomorrow—and “tomorrow” is closer than you think—you’ll describe what you need, and AI will fabricate a working application.

Not a prototype. Not a mockup. A working app.

This is already happening in primitive form. AI can generate functional code from natural language descriptions. The interfaces are clunky, the outputs require refinement, but the trajectory is clear: the bottleneck is shifting from “can you build it?” to “can you design it?”

The Architect Lawyer who understands software frameworks—who can describe a legal workflow precisely, who knows what’s technically feasible, who can validate whether the output actually works—becomes the designer. The AI becomes the fab.

And the designer owns the front door.

What This Means Practically

Think of it this way: You don’t need to be a carpenter to design a house. But you need to understand what wood can do, how load-bearing walls work, and what’s possible within the constraints of materials and physics.

The Architect Lawyer understands what AI can do, how data flows through systems, and what’s possible within the constraints of technology and regulation. They don’t write code—they write specifications that AI turns into code.

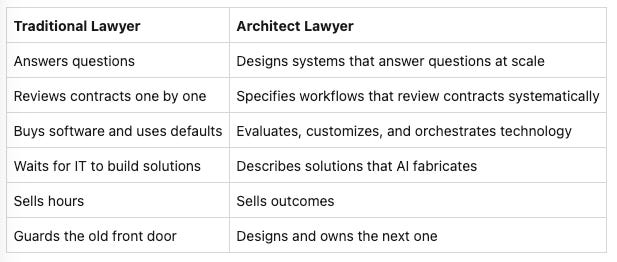

Here’s the distinction:

The Architect Lawyer thinks in systems, not tasks. They ask: “How do I solve this problem once, in a way that works for every future instance?” instead of “How do I solve this problem for this client, this time?”

This requires a new kind of literacy:

Technology evaluation: Distinguishing real capability from vendor hype

Workflow design: Understanding how to chain tools and processes for complex outcomes

Specification writing: Describing solutions precisely enough that AI can build them

Output validation: Recognizing when AI gets it right and when it hallucinates

Systems thinking: Seeing legal work as repeatable processes, not one-off engagements

This isn’t about becoming a technologist. It’s about becoming fluent enough in technology to direct it—today as a sophisticated buyer and user, tomorrow as a designer whose specifications AI fabricates into working solutions.

The partners at elite firms who command $2,000+ per hour aren’t doing document review. They’re architecting deals—structuring transactions, designing governance frameworks, engineering outcomes. They’ve always been architects. The difference now is that the output of architecture is changing. It used to be documents and advice. Increasingly, it’s systems and software.

The lawyers who develop this literacy won’t just survive the front door migration. They’ll own the next front door—not by guarding it, but by designing it.

The Choice in Front of You

The travel industry didn’t disappear when Expedia captured the front door. Hotels still exist. Airlines still fly. But the travel agents—the human gatekeepers who used to be the mandatory interface—largely vanished. The ones who survived found narrow niches: complex itineraries, luxury travel, corporate accounts. The routine bookings? Gone to software.

The legal industry won’t disappear either. Complex litigation will still need trial lawyers. Bet-the-company M&A will still need dealmakers. Novel regulatory questions will still need experts.

But the routine work—the work that makes up the majority of legal revenue—is moving to whoever controls the interface. And the lawyers who don’t understand this will find themselves in the same position as travel agents in 2005: confident in their expertise, dismissive of the threat, and blindsided when the volume evaporates.

Here’s the difference between lawyers and travel agents: lawyers can design the next front door.

Travel agents couldn’t build Expedia. They lacked the technical literacy, the software frameworks, the ability to even conceive of what was possible. By the time they understood the threat, Booking.com had already captured the interface.

Lawyers have a window. The AI models that will fabricate tomorrow’s legal applications are just emerging. The lawyers who develop software literacy now—who learn to evaluate technology, design workflows, and eventually specify solutions that AI builds—can own the next front door instead of renting access to it.

But that window won’t stay open forever.

What’s your next move? Are you developing the literacy to design the next front door—or waiting until someone else builds it for you?

Thank you for this post! I have been reading more on systems thinking and tech literacy. I was wondering if there are specific sources/books/articles you think that are really relevant?